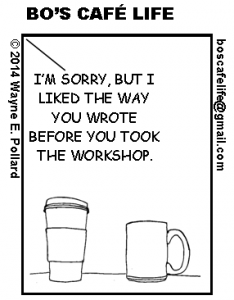

Graphic from Bo’s Cafe Life

Moderating a writer’s workshop at a con is easy. Someone has passed you the power to sit down and conduct. All you have to do is show up, say go, and let the people talk. Right?

Yes…but no.

Moderating a writer’s workshop well at a con is not so easy. The point of a workshop is not to see that a half dozen people get to talk on a manuscript; the point is to guide the workshop to help an author make a better manuscript. Workshops can do that, but they can also do the reverse.

I know of one instance where the writer went home, took the advice of one of the pros, and totally chopped up the manuscript. I was at the workshop so I heard the advice, and since I know the writer, I saw the result. The advice was a reiteration of something I’d said: writing structure should reflect writing content (a blog for another time). For instance, in the writer’s action scene, her sentences sometimes got away from her. They were longer and occasionally more rambling than they should have been for the situation: a gun fight in the forest. While these sentences were perfectly good sentences for the right situation, right there, they needed to be shorter, punchier, and more directed to the immediate events (no time to dissemble on stray thoughts). However, what and how the pro said it may have confused that writer for she went home and applied the advice to the whole manuscript to its detriment. Took her a few months to undo the damage.

You as moderator want to try to keep the workshop session focused on the goal of helping author-entrants to improve their works. The value of those works should not be under discussion. At one time, I had a writer’s group member make the comment in group about my work, “Ho hum, another Conan the Barbarian novel, but I guess you know that” (No, I didn’t, he is the only person to have ever said that—I left that group as a result). Another con workshop I heard about had an author-entrant writing about Norse mythos. A workshop participant compared her to Marvel’s Norse-influenced work and said they liked Marvel better. We writers need to follow our bliss, so don’t judge the author’s choice. Instead, guide each author to make his or her take on the subject his or her own unique story. So in your workshop, judge the intent of the stories and help the author-entrants meet their goals. If this type of judgment does happen, be prepared to gently redirect the attention to the intent and those goals.

Over the years, I’ve learned from my mistakes and successes to develop pretty simple guidelines.

Workshop Format

The science fiction and fantasy cons I’ve moderated for use the same format. The workshop comprises three author-entrants, two pros, and a moderator. Three manuscripts of up to thirty pages are delivered to all the workshop participants in advance to be critiqued in a three-hour session.

I will breakdown the process of a workshop using this format. If your workshop varies, you’ll have some math to do. This also assumes the room is yours for the full three hours. If it’s a dedicated room to the workshop, this is likely the case, but if a panel follows you, they will assume you were supposed to be out before the hour. To be sure, ask your program coordinator or look to see who is in the room after you.

Introduce yourself and that this is a workshop session. If more people are in the room than you expect, let them know it’s a private session. Go around the table and have everyone introduce themselves. I like to ask the pros to share their latest project—a moment of shameless self-promotion if you will. Set the rules for the workshop.

Rules

I’ve adjusted these guidelines from my college creative writing workshops. Each critiquer reviews the manuscript without interruption either from the other critiquers or the author-entrant. The critiquer whose turn it is to speak should not engage the others at the table (including the author-entrant) with questions unless the critiquer has a quick clarification he or she needs to make a point. He or she may then ask a question to elicits a very short answer from the author-entrant. You as moderator should be prepared to say, “let’s make note of that and address it further at the end” if the answer goes on too long.

The author-entrant will have time to ask questions. I like to stress that this workshop is for the author-entrant, not the critiquers. Author-entrants should not defend their work. After all, a shrink-wrapped version of the author does not come with every copy of the book sold. It’s not important that the critiquers understand what the author-entrant is trying to do, it’s important that the author-entrant understands what a reader may infer. No rebuttals or justifications are necessary and no good ever comes of such. If a critiquer is wrong, it’s just not that important that he or she knows. You as moderator may be called on to gently curtail an author-entrant who is trying too hard to defend the work. The only exception to this is if an author-entrant would like clarification on why a critiquer came to a particular conclusion. In this case, the author can outline the back information necessary to frame the question, ask where he or she went wrong, and inquire about suggestions to fix it.

Timing

- Each manuscript gets (about) 1 hour.

- Each critiquer will get up to 8 minutes to speak with a one-minute warning at 7 minutes. (I use my phone to have an alarm go off at the seven minute point. This way, I don’t clock watch, can remain engaged in the workshop, don’t lose track of time, and don’t have to personally interrupt folks.)

- 10 to 15 minutes of open table time starting with asking the author-entrant if they have questions. This will usually instigate an open table conversation. If it doesn’t, be prepared to ask questions to get conversation rolling.

- 5 minute break

Order

I give the order the critique will go in. This is really up to the moderator. I usually go clockwise, counter clockwise and clockwise again. However, some people may have never been involved in a workshop or feel insecure about going first, especially in the presence of pros. If one of the author-entrants is sitting left or right of you, you might inquire if they would prefer to go later (but don’t forget them! It’s quite embarrassing). Or you may just choose to start with one pro and move in a circle from there. Or you could determine an order before you even arrive and announce it when you start that critique. I tell people I will go last so that I can adjust for timing if it gets off.

I then announce the order of the manuscripts. Because of the workshop introduction, the first manuscript may go over the hour. You may wish to start with a manuscript that is shorter or you think might elicit fewer comments.

End of Workshop

Thank everyone for their time and participation. Remind the author-entrants to take time to think about and feel out the advice they have been given. They are here to learn, but ultimately they are the shepherds of their own work. They are the ones that need to guide it. Sometimes in experimenting with new ideas and ways of doing things, the writing can go wrong. So make a clearly marked back up of the story before massaging it. It will be liberating, allowing the author-entrant to push harder, and it will ensure that writing paths that lead to dead ends don’t lead to a manuscript’s dead end.