I’d been absent from the SF/F community for many years, and I’d decided it was time to reengage. So I volunteered for the writer’s workshop at Westercon. I was quite pleasantly surprised by one particularly engaging story about a haunted car and a repro man. Not only was the concept intriguing to me, but the writing was crisp and professional. I’ve been a fan of Brian Buhl’s writing ever since and hope that some day soon, more than just workshop participants will get to enjoy his stories.

Pride, envy, avarice – these are the sparks have set on fire

the hearts of all men.

~Dante Alighieri~

Writers are their own worst enemy. They wield distraction as a weapon, striking down their creativity with mighty blows. These distractions are often external, such as video games, social media, and cat videos. Honestly, who can resist images of adorable kittens, when the Internet is practically made of them?

Of course, not all distractions are external. From the primordial fluid of our imaginations crawl monsters and demons. These hideous creatures attempt to wrest the pen from our hands and shred our work in wicked fangs and claws. One of these monsters goes by the name of Fear. I’ve described him before, and how he tries to keep me from finishing my work by filling my mind with uncertainty and doubt.

Today, let us examine his cousin, Pride. For purposes of this discussion, I may refer to pride by other names, such as audacity or avarice. These are not the same thing as pride, but as distractions, they are borne from the same place.

Pride works against writers differently than fear. Fear tears the world down around the writer, making every step uncertain. Pride, on the other hand, blinds the writer, closing off options the writer might otherwise consider.

Imagine receiving unfavorable feedback from a writing group or editor. Imagine yourself saying something like, “But it’s my story! They just don’t get it!” That’s pride, my friend. That’s your ego inflated to the point that it is obscuring your vision, concealing the merit of the critique from your more critical mind.

I struggle to suppress reactions like this from time to time. We’ve all been there. We pour ourselves into our stories, breathing life into characters and living with them for weeks and months. We sow ourselves into our stories, so when our stories are “attacked,” it feels like the attack is personal. When someone reaches out to try to improve our work, pride refracts the message and distorts it, turning it into “your story isn’t good enough, and by extension, neither are you.”

Over time I’ve learned that this type of pride is like a bruise. If I walk away from the critique for a little while, the swelling goes down, and I’m able to see clearly again.

Fear and pride differ in another very important way. As a monster, fear is a giant spider that catches you in sticky webs. It ties you up, bites, and fills your veins with poison. Pride, on the other hand, is a powerful wolf. You have to respect them both. But where fear seeks to destroy you at every turn, pride can be tamed. Pride can be your ally.

Consider what it is sell a story. You are stating with a loud, clear voice that the product of your imagination, the words you’ve sewn together to form a unique whole, is worth time and money. You’re saying that other people should close YouTube and the world of cat videos long enough to focus on your story. What audacity! What arrogance!

Fear wants to tell you that your work isn’t good enough, but pride comes to your defense. Of course your story is good enough! You wrote it. Instead of calling this pride, we call it self-confidence. Instead of blinding us to what we should see, it shields us from lies designed to tear us down.

Even when we’re not crafting our stories, pride prowls alongside the writer, always ready to cause trouble. Consider George Lucas. Watch documentaries early and late in his career. In the early documentaries, while his star was still ascending, he can be seen consulting with his actors and crew, looking directly at them. Compare that to later footage after he’d reached the peak of his success. Watch his body language, and watch the faces of the people around him. Young Lucas looks like he’s more engaged with the people making a film with him. Elder Lucas appears to be surrounded by people that are wary and uncomfortable, and he doesn’t seem to notice. That is pride, filling the creator with visions of his greatness to the point that he can no longer see what’s going on around him.

To be fair, those documentaries only show us what the camera sees. We can’t really know with certainty what ran through George Lucas’s mind, at either point in the famous director’s career. But the tale of pride leading a creator astray is not a new one, and it makes a lot of sense in this case.

Fame and monetary success are not requirements for pride. Pride is present as soon as the writer declares themselves as someone with more than just a writing hobby. It becomes part of our identity in the same way we sow ourselves into our stories.

For example, an easy way to get my dander up is to call me a “young writer.” I’ve been writing for more than 25 years, with more than one completed novel sitting in a drawer. My pride straightens my spine and inflates my lungs with air, ready to bellow loud and strong that I’m experienced, and how dare anyone insinuate otherwise.

The reality is that I am still a young writer, and it’s not an insult. I’m slowly and methodically improving my craft, learning how to improve. Pride may want me to strut and preen, but that won’t clean up my unsold stories. Pride isn’t going to make me more creative.

But pride can help me put my work in front of other people, because pride overshadows fear.

And with that said, I must thank my friend Jennifer for inviting me to guest on her blog. It is the sort of gesture that feeds pride and keeps it healthy. For to tame pride and make it work with you instead of against you, pride must be kept on a short leash and given the nourishment of praise.

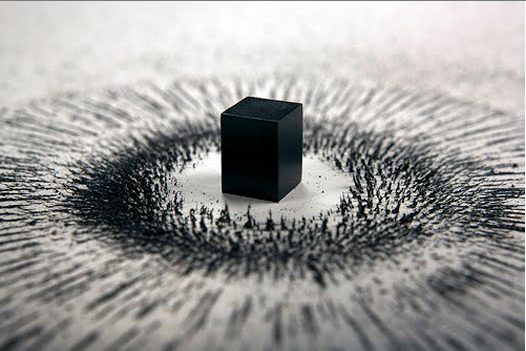

Pride, like the magnet, constantly points to one object, self; but unlike the magnet, it has no attractive pole, but at all points repels. ~Charles Caleb Colton~

Brian is a full-time programmer living in Northern California. He plays alto saxophone in the River City Concert Band. He’s been married about twenty years and has two children. He writes science fiction and fantasy often at his local coffee shop. He’s been writing off and on for more than 25 years. His blog is mostly about writing, and his journey to changing from a guy with a writing hobby to a professional author.